Font of Wisdom

© 2000 Lawrence I. Charters

Washington Apple Pi Journal, March/April 2000,

pp. 21-23, reprint

information

Macintosh computers have been with us for a long time,

but most people still don't know how to use them properly.

Not just a few, mind you, but: most.

As proof, just look at almost anything written by Mac

users over the past decade and a half. Given that the

Macintosh almost single handed (neat trick for a limbless

computer) revolutionized the world of typesetting, it is

shocking to see how many letters, memos, reports, and other

bits and pieces of text produced on such marvelous machines

look like they were produced on: typewriters.

While this aberration is most pronounced in and around

Washington, DC (where "innovation" often means getting rid

of the new and going back to the old), this blight is

present almost everywhere. Hardly a day goes by without a

church flyer or some other organization brochure falling out

of the mail, printed in several different sizes of Courier,

a monospaced font invented for the IBM Selectric typewriter

(in 1961). Or entire letters written in Chicago, a font

designed (in 1983) specifically for the Mac's menus, and

nothing else.

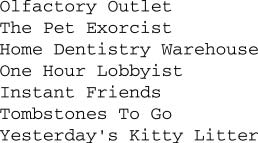

So, as an intellectual exercise, let us consider a

brand-new shopping mall that wants to promote its stable of

upscale stores for the discriminating shopper. Here is how

the federal government would list the stores, using Courier,

of course:

While there is nothing wrong with such a list, it tends

to look sterile and colorless. Another problem with Courier

(and all other monospaced fonts) is that it is harder to

read: the eye has to travel the same distance for thin

letters, such as j, as for wide ones, such as w. This makes

it more tiring to read things written in Courier, as the

eyes must travel farther and work harder.

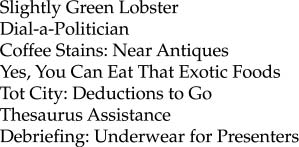

Listing the stores in Palatino, a popular serif font,

adds an almost instant elegance:

Palatino, by the way, is the font used for body text in

the Washington Apple Pi Journal. If you take a look

through your home, you'll soon discover that virtually every

book, magazine, and newspaper uses a serif type for body

text. Government reports, of course, usually use Courier,

since they are apparently supposed to be hard to

read.

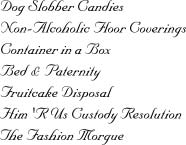

Some people take the idea of "elegance" a bit too far,

and use calligraphic fonts to "add style." Calligraphic

fonts are definitely elegant, subtly suggesting days of yore

when all text was written by hand using quills:

Before you write something in a calligraphic font (in

this case Nuptial Script), there are a few things to keep in

mind. First, writing with quills is hard on geese. Second,

calligraphic fonts are hard to read. While it might be fine

for a once-in-a-lifetime event, like a marriage, for lesser

purposes it is exasperating. Roughly once a week, a letter

or a flyer arrives in the mail written entirely in

calligraphic fonts (note: usually more than one). These are

quickly dispatched to the recycle bin, unread.

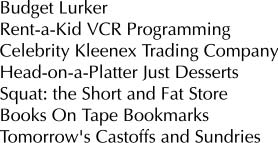

This does not, of course, mean that everything should be

written in Palatino and other serif fonts. Traffic signs,

for example, are always written in sans-serif fonts: they

have simple messages, and want to make their point quickly

and emphatically. In our upscale mall, the mall directory

would be a good place to have a sans-serif font, such as

Optima:

Optima, and other sans-serif fonts, should not be

overused. Some Web sites, for example, use sans-serif fonts

for everything because it looks different.

Unfortunately, it doesn't look different if overused; it is

the contrast with serif type that makes it look different.

An important point to consider: while very small children

might read letter-by-letter, literate readers read by the

shapes of words. Serif fonts, such as Times (the most

popular font in the world), Palatino, and Garamond (all

Apple advertising is done in Garamond), are easier to read

in small sizes. The serifs at the end of strokes make the

letters more distinctive, giving the words more of a shape.

Using proper capitalization also gives the words more shape.

To illustrate this, consider the worst abuse of

typography in the 20th century: the Surgeon

General's warning on packs of cigarettes. Ordered to put the

warning on all cigarette packages, the tobacco companies

decided to comply in such a way as make the warning all but

unreadable. The warning was reproduced in a san-serif font,

all upper-case, with a heavy border and unnecessary lines

thrown in, thwarting any attempt to "read by shape:"

Insurance contracts, credit card applications and other

forms use a similar tactic, making sure to obscure the parts

they really don't want you to read by writing them in tiny,

sans-serif type, all in upper case letters. "Combat

typography" must be a required course in marketing programs.

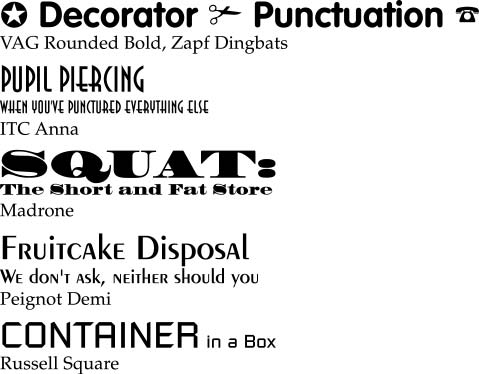

But our upscale shopping mall doesn't want to drive

customers away. Instead, we want to invite them in to spend

money, and one of the least expensive ways to do this is

through good use of typography. Good places for distinctive

typography are the signs above the store entrances:

Good typography, of course, shouldn't be limited to mall

directories or store entrances. While the body text of

brochures, leaflets, flyers, business letters and such

should aim for effortless clarity, the name of the business

-- reproduced on those same items, plus business cards,

bumper stickers, coffee mugs and other common corporate

paraphernalia -- should exhibit some creativity.

Keep in mind, too, that most of the printed world is

still black and white. A recent flyer, announcing the

retirement of a coworker, was printed in six different

colors, with six different sizes of type. Six different

colors and sizes of Courier.

Wouldn't it have been easier to read (and photocopied

much better) to write it in a careful mix of serif and

sans-serif fonts?

Further reading

Almost every issue of the Washington Apple Pi

Journal lists the programs, hardware and fonts used to

construct the Journal, usually on page 3. Flip back a

few pages and take a look. Then see if you can figure out

why we made these choices. Then tell us; we crave

reassurance.

An introduction to fonts was published in the

Journal during the 1900s, "Fonts: An Overview,"

Washington Apple Pi Journal, pp. 29-32, May/June

1999. This covers such topics as the differences between

serif, sans-serif, calligraphic and other kinds of fonts.

If you are a new Macintosh user, or a veteran Macintosh

user, or you have never, ever used a Macintosh, take a look

at Robin Williams' The Little Mac Book. Now in its

sixth edition, this is the best computer book yet written:

it presents a mass of technical information in a

non-technical, non-threatening fashion, with subtle,

splendid illustrations. There is an entire chapter devoted

to fonts that, quite frankly, doesn't touch on any of the

topics covered here. But she does tell you how your Mac uses

fonts, as well as thousands of other useful things.

Most personal computer users don't really understand how

to even type on a modern computer, much less a Macintosh.

Common punctuation, tabs, margins and other essentials

baffle them (and it shows). Robin Williams addressed these

concerns in her first book, The Macintosh is not a

typewriter, an excellent, slender volume just as

valuable today as it was a decade ago.

If you've mastered the lessons of these books, you are

ready for some heavy-duty typography, which Robin Williams

covers in two more books, How to Boss Your Fonts

Around, 2nd ed., and The Non-Designer's

Type Book. The first discusses font management on the

Macintosh: what fonts are, how they work, how they are

stored. The second discusses typography as an aesthetic as

well as an applied art form, with outstanding examples of

how to look sharp using nothing more than tasteful

typography (and talent).

You might ask: haven't other people written books about

fonts and typography? Certainly. They just aren't as good.

Robin Williams, The Little Mac Book,

6th ed., Peachpit Press, 1999, 445 pages, $19.95

Robin Williams, The Mac is not a typewriter,

Peachpit Press, 1990, 72 pages, $9.95

Robin Williams, The Non-Designer's Type Book,

Peachpit Press, 1998, 239 pages, $24.95

Robin Williams, How to Boss Your Fonts Around, 2nd

ed., Peachpit Press, 1998, 188 pages, $16.95

|