Because It's There: Linux

on Virtual PC

© 2000 Washington

Apple Pi Labs

Washington Apple Pi Journal, March/April 2000,

pp. 44-46, reprint

information

Washington Apple Pi Labs has always

enjoyed challenges. From the very beginning, whenever that

was, we strove to do the impossible, the improbable, and

sometimes the clearly silly. When we first got our hands on

a gigabyte hard drive, for example, we immediately plugged

it into a Macintosh IIfx (at that time, the file server for

the Pi's bulletin board, the TCS), and set virtual memory to

a full billion bytes. Then, flush with all this imitation

memory, we launched, simultaneously, every single

application we could find, even going so far as to install

an extra 20 or 30 so we could have them all running at

once.

|

|

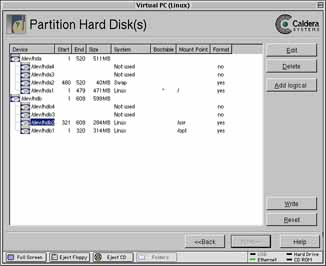

The advanced partitioning

options of the OpenLinux 2.3 installer were used to

create several partitions in Virtual PC 3.0. This

is not for the faint of heart (and, in fact, this

partitioning attempt proved to be unsuccessful).

Note the Virtual PC icons at the bottom of the

screen, used for changing the screen size and

accessing various types of media.

|

It was grand and glorious, a prime

example of conspicuous computing. It was also painfully slow

and, admittedly, without a readily identifiable purpose,

particularly when we ran out of applications before using up

more than a third of the memory. So: why?

|

|

|

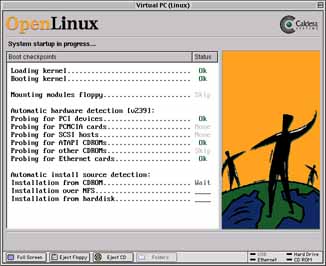

During the installation

process, the installer checks out the (emulated)

hardware to see what "devices" are available. A

device, in typical UNIX fashion, can be something

physical, such as a CD-ROM drive, or a "logical"

device, such as a hard drive partition.

|

Why would anyone in their right

mind want to install an Intel version of Linux on a

Macintosh? Since the Mac doesn't use an Intel central

processing unit (CPU), this seems a strange thing to do,

especially when there are perfectly good PowerPC-specific

versions of Linux available. So: why?

|

|

|

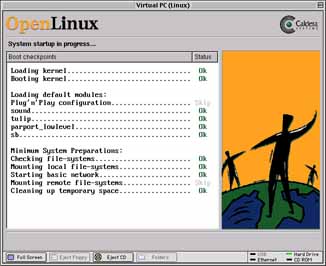

After installation,

instead of colorful (and cryptic) startup icons,

Caldera's version of Linux offers nice, clear (and

still cryptic) milestones of where it is in the

boot process. The "Plug 'n' Play" and "tulip"

milestones are the target of frequent humor.

|

George Mallory, attempting to climb

Mount Everest in 1924, was asked the same simple question:

why? "Because it's there" was his famous answer. On June 8,

1924, Mallory disappeared on Everest. Seventy-five years

later, on May 2, 1999, Mallory's frozen body was found on

the mountain. No one knows if he ever made it to the

top.

|

|

|

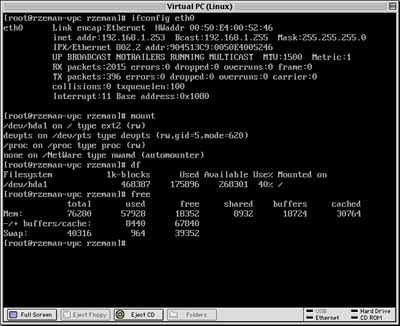

Once Linux has initialized

and you've signed on, you have the option of

opening up a terminal window (tty console) and

trying out the famous, easy to understand UNIX CLI

(command line interface).

|

Half a world away and several miles

closer to sea level, Washington Apple Pi Labs still thinks

Mallory had the right idea: "Because it's there." Or at

least it might be, given a late-model translucent-cased

Power Macintosh, lots of memory, lots and lots of free hard

drive space, Virtual PC 3.0 from Connectix, and one of the

many "commercially packaged" versions of Linux. So on a

frozen January morning, with the entire East Coast shut down

by a surprise blizzard, Washington Apple Pi Labs attempted

something you probably don't want to ever do

yourself.

|

|

|

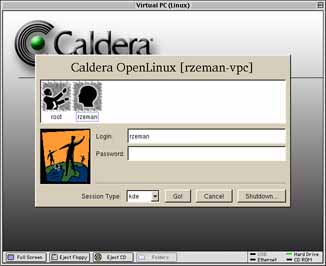

Every time you boot, you

are presented with a graphical dialog box asking

for name and password. Note the pop-up menu in the

lower left offering you a choice of interface

types.

|

And, since you also probably aren't

interested in anything other than the pictures, we'll offer

just an executive summary. First, Virtual PC was used to

create an emulated Pentium computer. Next, the default

Windows operating system was blown away. Next, the Linux

installer application was fired up from CD-ROM, and Linux

was installed. And installed. And installed. (It takes a

while.)

|

|

|

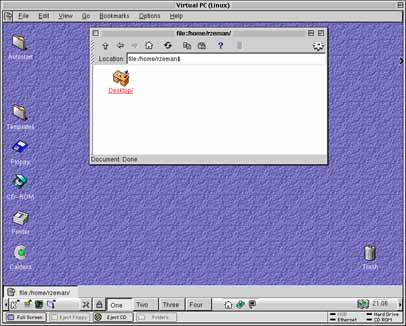

If you select KDE (which

stands for "K Desktop Environment") when you first

log in, you are presented with this cheery

graphical user interface, patterned after the

browser mode of Microsoft Windows 98. Thus, after

hours of work, you can stand proud, knowing that

you have a UNIX emulation of Windows 98 running on

an emulated PC running on a Macintosh. The "K" in

KDE, by the way, apparently stands for nothing

other than the letter between "J" and "L."

|

Many hours later, we had reached a

conclusion: yes, you can run Virtual PC 3.0 and, within

Virtual PC, fully install and operate Linux. If you wish,

you can even run one of the Windows-like graphical

interfaces to Linux on your emulated Pentium running on your

Power Macintosh, complete with network services. Of course,

it redefines the word "slow," but it does work.

|

|

|

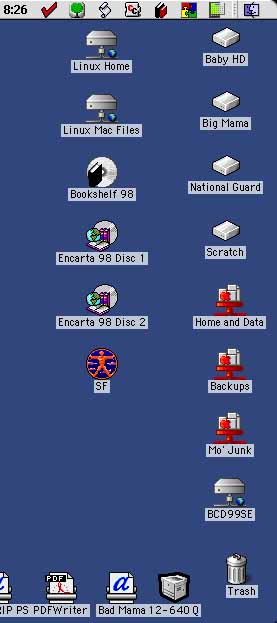

7.virtualdiscs.tiff: While

not directly related to this project, this window

shows a "good use" for a Linux machine: CD-ROMs

saved as Linux disk images, mounted under Linux and

shared over a network via netatalk so they can

appear -- and be used -- on a Macintosh desktop.

Yes, there are less Byzantine ways of doing the

same thing, but they probably aren't nearly as

entertaining.

|

It is also a safer way to spend

your time than climbing nearly six miles into the sky

without oxygen. Why do this? Because it's there.

|

![]()